HIROSHIMA memory keepers Succeed to history

Vol. 11 2017.7.27 up

History goes on, and the past and the present are never separated. We need to realize it and pass what happened down to the next generation.

Mrs.S

anonymous

What do people handing down the experience of the A-bombing think and try to convey?

We interviewed Mr. S, 72, who worked for the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital and A-bomb Survivors Hospital for 25 years and as a social worker, dealt with survivors’ suffering and problems in their lives.

Section

Job as a medical social worker

When did you start to work as a medical social worker?

I started in 1968, when I was 23. I joined the Red Cross Hospital, wishing to help people who had mentally and financially suffered in their lives so that they could return to society.

Tell me about your job.

In 1957, 12 years after the A-bombing, the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law was enacted, and the A-bomb Survivors Hospital opened, where people having an official certificate as hibakusha could receive treatment under the law. Then, in 1968, the A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law was enacted, aiming to support survivors. It allowed them to receive compensation money. Under the law, people needed a certificate from a doctor to receive support. My first job was to check whether they were eligible for compensation money.

Did many survivors come to your office to get compensation from the government?

Yes. For about 20 years after the A-bombing, survivors died one after another, and many were struggling to start their lives again in Hiroshima. The closer to the hypocenter people were, the more severely they were affected by the blast, heat rays and radiation. Many of them had lost the foundation of their livelihoods and could not continue to work. In the situation where they were completely deprived of their livelihoods, their jobs and families, they expected a great deal from the A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law. The hospital was crowded with people claiming compensation and support.

What were the conditions necessary to receive benefits?

Roughly, there were three: having disorders caused by A-bomb radiation, age and income. Nearly 50 people came to my office every day, but most of them were not eligible, and we could not give them any compensation. I was seized by a sense of helplessness; “Why is this kind of thing still happening even 23 years after the end of WWII? —What can we do for survivors? — Nothing!”

Trying to help survivors, I started the Hibakusha Problems Caseworker Group in 1973, together with counselors of the Japan Confederation of A-and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations and medical facilities in Tokyo, Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Damage and injuries caused by the A-bombing did not end just on August 6 and 9

Could you tell me about your group?

First, we made a list book in which each survivor’s experience was collected and organized in such sections as “Life before the A-bombing,” “Damage and injuries on that day,” “Life after the A-bombing,” “Sufferings” and “Changes in society and system.” We tried to get an overall picture of the A-bomb damage, based on each individual survivor’s experience.

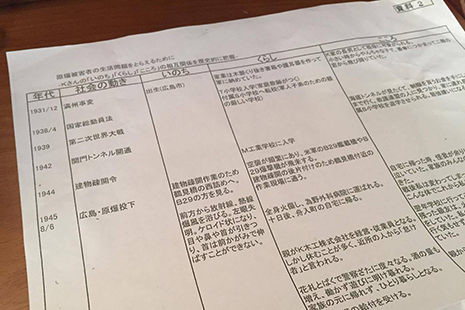

Among the materials you brought today, you have one with the title, “A chronological table of change in society, life and thoughts.”

We made this one based on the system taught by Dr. Tadashi Ishida, the late professor of Hitotsubashi University who specialized in social surveys. We tried to understand survivors’ experiences from the viewpoint of their “life, living and feelings.”

For example, some people died because of radiation although no wounds were found on their bodies. So, we looked at it from their “life” angle. From the viewpoint of their “living,” we looked at what kind of life they had before August 6, 1945, how their houses, workplaces and families changed after the A-bombing, and how the society changed around them. From the viewpoint of their “feelings,” we focused on how survivors responded to what had happened to them.

Basically, we pursued their feelings.

The A-bomb damage and injuries did not end just on August 6 and 9. Some people had no choice but to have a desolate life because of their sufferings caused by the A-bombing. Others could not receive aid because of the limited social relief system.

On the other hand, it is true that some people overcame their suffering, supported by other people. We analyzed and outlined how survivors’ feelings changed as society changed.

People tend to focus on just the day when the A-bomb was dropped. However, we can see how what happened on August 6,1945 has affected each survivor’s life, by looking at them from the viewpoint of their lives, living and feelings.

Dr. Tadashi Ishida, from whom we learned the style of the survey, also investigated the effects of the A-bombing on survivors. He painstakingly continued his investigation by talking to survivors who felt toyed with by the A-bombing and were struggling.

There are many survivors who have felt guilty because they could not help other people on that day. That is not something they have to take responsibility for, because those people’s suffering was caused by the A-bombing. But by looking at the fact of the A-bombing and their struggling, they eventually could overcome their sense of guilt. Dr. Ishida earnestly investigated the changes of their feelings and its process.

People were affected by the A-bombing, not only on that day, but their suffering has continued since then until today. By looking at each case carefully, we can see the whole range of damage caused by the A-bombing.

Mr. K’s experience

I am sure you were consulted by many survivors. Do you have someone you remember well?

Mr. K, who suffered from hepatitis caused by alcohol dependence, was hospitalized in the A-bomb Survivors Hospital where I worked at that time. He had to go to the welfare office to get money, but he couldn’t go and came to me for some advice. I went there and received money for him, and he started to take counseling from me.

I met him when he was 42. He was A-bombed at the age of 13. He had keloids on his face and his left eye was an artificial one because of a malignant tumor. At first glance, we could see that he was badly injured by the A-bombing.

When I gave the money from the welfare office to him, he was very pleased that I went to the office for him. He said, “I am filled with an inferiority complex.” The day he received the money, he left the hospital without permission and went home. I was shocked, so I wrote a letter to him, wishing that he could bounce back from his tragic experiences.

What did you write in the letter?

I wrote; Seeing your keloids, I can imagine that you were severely injured by the A-bombing. I think you have had a hard time since then. But precisely for this reason, you understand the suffering and sorrow of many survivors. I would like you to live with confidence.

Mr. K treasured that letter until he died. He said that he read it whenever he had a difficult time. I think that he felt isolated from society, blamed by his family and could not meet anyone who accepted him and his injuries.

After I sent the letter to him, he often came to see me and started to talk about his A-bomb experiences.

Before the A-bombing, he was an active boy and raised with much affection as a successor of his family by his parents and grandparents.

On August 6, 1945, Mr. K was working at a demolition site near the Tsurumi Bridge. Before the roll-call, he saw a parachute falling from a B-29. He was directly exposed to heat rays, and severely burned. His family were lumber merchants in Funairi. As his house was completely burned, they evacuated to Miayajima Island and his mother looked after him there. After a while, his burns healed, but his keloids remained. He didn’t want to go to school, and his life started to fall apart. He was often taken to the police station because he gambled around the station.

As he got weaker because of radiation, he couldn’t work. He pilfered money from his house and used it on gambling repeatedly. Finally, his parents didn’t let him into the house.

Mr. K met you, and he gradually opened his heart to you after he got your letter, didn’t he?

Yes. One day, I asked him to talk about his experiences on August 6 to children on a school trip. He hesitated at first, so I went with him and helped him during his talk. He seemed to be encouraged by the letters he received from students who heard his story. He continued to talk about his experiences, listened to other survivors’ experiences and even visited some survivors who had problems.

I think that Mr. K realized what living as an A-bomb survivor meant to him.

He started to work, declined the welfare money and stopped drinking. Then, he got married. He had been disowned, but his parents and brothers noticed his changes and accepted him back.

He started to write his own history, in addition to talking about his experiences. I heard he had kept writing the details of his history in his bed until he died at 65.

I got a message from a lady in Tokyo who heard Mr. K’s story.

She wrote: “I thought it is human beings who bring other human beings to the bottom of misfortune, but it is also human beings who give them hope of living. Although he had a hard time after the A-bombing, he finally recovered and led a good life. That was because he was brought up with much affection from his parents and grandparents and supported by many good and considerate people.”

Feeling empathy toward survivors as human beings

How did you feel when you saw survivors change by looking at their own experiences?

They have tried to hand their experiences down to the next generation, wishing that such things will never happen again. They also look at their lives and tackle their own problems by writing and talking about their experiences. I think passing their experiences down in some way is also meaningful to survivors themselves.

What is important when young people look at survivors’ experiences, other than the three viewpoints of life, living and feelings?

I think that feeling empathy with their experiences as a human is important.

History goes on, and the past and the present are never separated.

Young people must realize that and pass what happened to us down to the next generation.

They must learn something from survivors’ experiences as messages to them. If they feel something from survivors’ stories and learn some lessons, they can hand them down to the next generation.

Thank you for your precious story.

Interviewed on June 2017.

About

"Interviews with HIROSHIMA memory keepers" is a part of project that Hiroshima「」– 3rd Generation Exhibition: Succeeding to History

We have recorded interviews with A-bomb survivors, A-bomb Legacy Successors, and peace volunteers since 2015.

What are Hiroshima memory keepers feeling now, and what are they trying to pass on?

What can we learn from the bombing of Hiroshima? What messages can we convey to the next generation? Please share your ideas.